Our History

About Swenson Stone Works

The Swenson Tradition

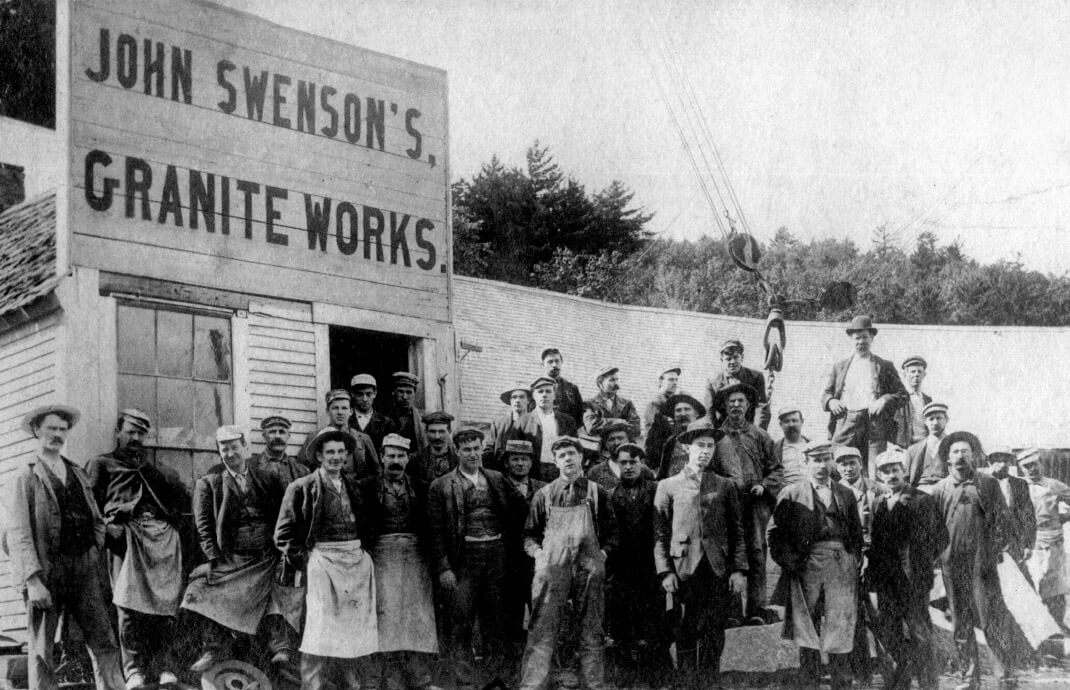

Since 1883, the Swenson Company has provided granite for numerous monuments and prestigious projects around the country, including parts of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, the Brooklyn Bridge, and the Pentagon. At the center of it all for three decades was John Swenson.

A Rock-Solid Legacy

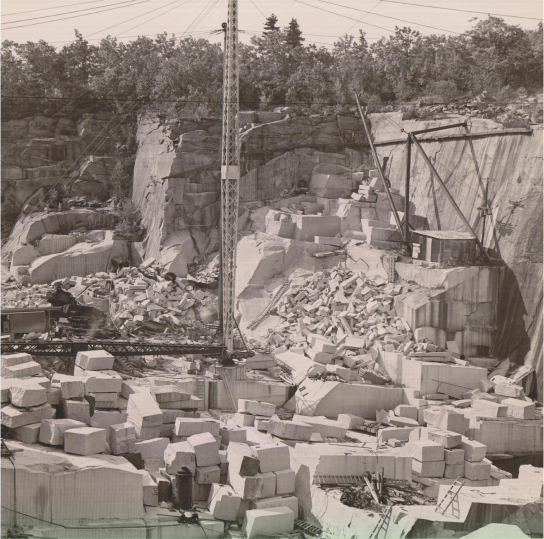

When the word granite is mentioned, it brings to mind other words, such as solid, grounded, unyielding and set in stone. When the term The Granite State is mentioned, that brings to mind New Hampshire, and in New Hampshire, the word granite stands for something just a bit more. It stands for the industry that was borne in the late 1800’s, in the city of Concord, on Rattlesnake Hill. That’s the place where three large boulders were discovered and purchased, for the purpose of producing granite monuments.

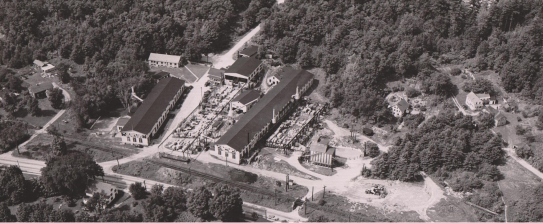

The type of granite in these boulders would later become known as Concord granite. Noted for its fine texture and lack of imperfections, Concord Granite was the standard by which other places judged their own granite. By 1900, 44 separate stone companies were pulling granite from the quarries on Rattlesnake Hill, high above North State Street.

The Swenson Stone Company

Gradually Became The Strongest

Of These Companies

The Swenson Stone company gradually became the strongest of these companies, and purchased other regional quarries to expand their capabilities and market appeal. The Swenson Company has provided granite for numerous monuments and prestigious projects around the country. These include parts of the Tomb of the Unknown Solider, the Library of Congress, the Brooklyn Bridge, The Pentagon, and Civil War monuments from Gettysburg, Pennsylvania to Antietam, Maryland.

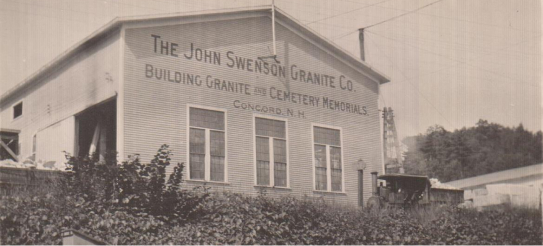

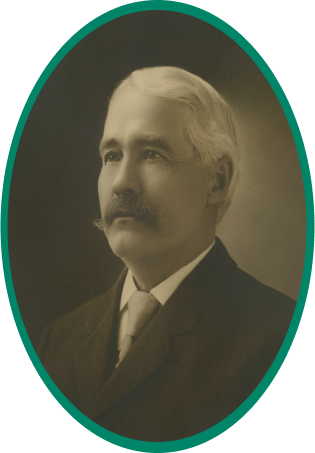

For three decades, one man was at the center of it all. John Swenson became one of the state’s most important quarrymen, an immigrant who came to town, learned a trade, and started a successful business that endures today.

“Few men of his generation have contributed as much to the industrial up-building of the City of Concord as the late John Swenson, a self-made man of many friends and a national reputation for ability and integrity, who carved for himself from Concord granite a career, a fortune and a business employing hundreds of men at good wages,” wrote a Concord Monitor editorialist in 1918, shortly after the brawny Swede died.

Today, John Swenson’s descendants talk more plainly about his legacy. “If we’re important in the history books, it’s because we survived and the others didn’t,” said David Swenson, a grandson who worked for the company for many years.

But historians recognize John Swenson as someone pivotal in the state’s long and varied granite tradition.

“Four generations later, the Swenson Stone Company is the heir to Concord’s distinguished stone quarrying tradition,” said Donna Belle-Garvin of the New Hampshire Historical Society. “John Swenson started out modestly, just one of many, but he persevered, and his company became a leading producer of building granite in the country.”

Growing Prominence

John Swenson was born in 1851 in Falkenberg, Sweden. His father had a small farm and a relative ran a brewery. An ambitious boy, John Swenson set sail for America and bigger things at 19 years old.

He worked near New York City where he met his wife, Ellen Anderson. They soon moved north of the city where John worked on a farm and then for a gas company.

Eventually, the Swensons made their way to Kansas City, near relatives, where John worked as a laborer on the railroad. The stay in Kansas was not long, as John’s “health was adversely affected, he claimed, by the drinking water,” a relative recalled.

Later, as the family became more prominent, John was elected to the New Hampshire House and then the Senate. He loved to play poker, and invested in the stock market and speculative land deals with lawyer friends.

At one point, he bought a Cadillac, and parked it at his North State Street home, in a two-car garage that had its own gas pump, a sign of marked success. “He seemed to be of a rather serious nature,” recalled a grandson of John Swenson in a 1988 family history. “One winter day, when I was in Harry G. Emmons’ store with my mother, he descended the staircase wearing a coonskin coat in which he seemed mammoth to me.” Re-called a grandson, also John Swenson, in a 1988 family history.

“Upon spying me, he broke into a broad grin and withdrew from his pocket a 25-cent piece which he placed in my hand, in spite of the protestation of my mother that such a sum was unreasonably large.”

Heavy Lifting

The road to success in granite was not easy. “Nothing is ever easy in granite,” said David Swenson.

In the past, when drilling was done by hand, the process was long and discouraging due to poor breaks in the rock or spoiled patterns. To lose a pattern after many days of drilling was more than just a setback – it was costly.

“Prospecting for quarries is carried out with as much enthusiasm as prospecting for gold mines,” Josiah Dyer wrote in an 1899 Granite Monthly magazine article.” The blanks are more numerous than the prizes.”

On cold nights, John Swenson would come home and rig a typewriter across the bathtub upstairs to “do the books” or write letters to customers and keep warm.

By 1904, John had built a strong business and asked his eldest son Omar, who was living in Boston, to work with him.

The younger sons soon followed, as the company began acquiring Rattlesnake Hill piecemeal. First the Hollis Quarry, then the Railway Quarry, from which came better rock for both monumental and building purposes, and on and on. Today, the company owns about 100 acres on the hill.

Swenson’s workers were an eclectic lot. Many, like him, were Swedish immigrants.

In fact, by 1910, 385 native-born Swedes lived in Concord – 18 out of every 1,000 residents. By the early 20th century, the granite industry also employed Native Americans, Irishmen, Englishmen, Scots, Scandinavians, Italians, Armenians and French- Canadians.

The work was taxing. Stone was hauled down the hill on heavy wooden wagons drawn by four powerful Belgian horses until 1918, when a steam wagon was used. Today, trucks do the work.

When the Library of Congress was built in the late 1800’s, 300 men worked six years to split and finish the 350,000 cubic feet of granite needed to fulfill the contract. The granite was transported from Concord to Washington in 2,200 railway cars. It still stands as the most monumental structure ever erected of Concord granite.

During John Swenson’s era, the main use of the stone was fabrication of monuments, with some steps, base courses and mausoleums.

But, in 1894, the company got its first major building contract, supplying the stone for the First Church of Christ Scientist in Boston, a landmark building that became the “Mother Church” with the Christian Science world headquarters. That contract set off several decades of supplying building granite all over the country.

When John Swenson died, he left a company poised to enter its most expansive building period.

Tiffany’s and CBS

Swenson had opened a sales office on Fifth Avenue in New York, and company agents were dispatched to Chicago and St. Louis, ready to take orders.

To satisfy architects’ taste for different colored granites, the company combed the world and offered 18 different colors over the years. Besides Concord’s gray granite, the company supplied soft pink, green, brown and black granite from Maine, white from Vermont, imperial pearl from Sweden, black from Brazil, mahogany from South Dakota, black from Canada and blue from Australia.

The Great Depression was the beginning of the end of the great granite boom. With the growing popularity of steel and concrete as popular building materials, demand for granite waned. By 1932, only two quarries remained on Rattlesnake Hill.

In 1941, Swenson became the lone survivor. Still recognized as the most weather-resistant material, granite became more popular as a veneer overlay, usually about an inch thick. Granite wall foundations, with a 4-foot thickness at the base, became a thing of the past.

The Swenson Company supplied granite for thousands of buildings. Here are a few:

- The Waldorf-Astoria Hotel

- Tiffany’s Jewelry store

- Seagram’s building

- CBS Broadcasting’s “Black Rock”

- The Ford Foundation

- The step of St. Patrick’s Cathedral

- The Beineke Rare Books

- Manuscripts Building at Yale University

- Amon Carter Museum in Texas.

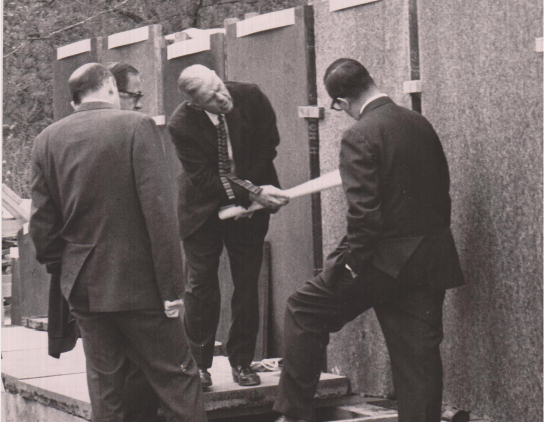

When CBS President William Paley and architect Eero Saarinen built the broadcasting company’s 491-foot high headquarters in the 1960’s, they looked at 50 different types of granite before settling on Canadian black granite that Swenson supplied.

Over the years, the Swenson company has dealt with labor problems, strikes, and many occupational hazards such as a chronic lung disease called silicosis, caused by particles contained in granite dust.

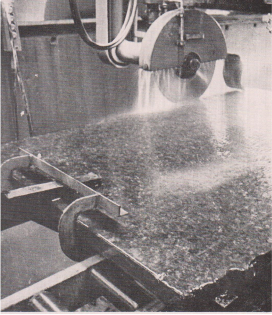

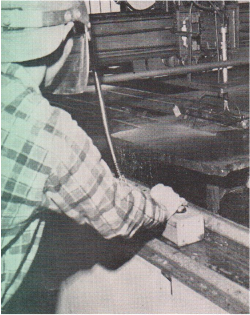

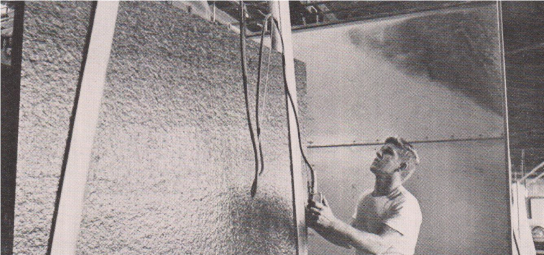

The Swensons played a pioneering role in protecting workers. In 1923, the company installed a dust-gathering machine in the plant. In the 1940’s, the company introduced an experimental therapy using aluminum dust as an antidote. Today, water is utilized extensively, along with modern sawing equipment, to eliminate the health concerns of granite dust.

Endless Supply

With the development of the interstate highway system in the 1950’s and 1960’s, curbing became the leading product of the Swenson Company.

By the mid-1970’s, with the increase in foreign competition, a soft building market and a continued waning popularity of granite as a major structural component in buildings, Swenson bowed out of the production of building stone and focused on curbing.

Granite, even today, is considered the best material for curbing. It doesn’t break down as easily as asphalt or concrete.

“Nothing can stand up to the salt and winter roadways like granite.” said Kevin Swenson, who took over the company’s operation and purchased several granite operations with his brother Kurt in 1974.

In 1984, Swenson Stone Works Company purchased the Vermont-based Rock of Ages Corp., making them the largest quarrier and granite memorial manufacturer in North America. With the shift in manufacturing emphasis, the company also returned to manufacturing monuments as in the John Swenson days.

In 1997, The Rock of Ages Corporation became a publicly traded company on the New York Stock Exchange, though the Swenson family still holds a controlling interest in the company. Although it still sells rough granite blocks to other manufacturers of building materials, the Concord operation mainly produces road-curbing material.

A retail operation was formed in 1989, with the opening of the first Swenson Stone Works store at the base of Rattlesnake Hill. Other locations would follow in Amherst NH, Westbrook ME, Medway, Rowley, and Hanover MA, Newtown CT, and North Kingstown RI.

In 1997, the Swenson Company purchased the Anderson-Friberg production facility in Barre, VT.

This move has allowed the company to streamline their operations, and to offer an expanded array of durable and economical landscape and masonry products, to satisfy the high demand from the contractor trade as well as homeowners. Swenson Stone Works produces and stocks a complete line of steps, posts, benches, bird baths, fountains, pavers, edging and more, to satisfy its customers’ needs. Swenson also works with its customers to custom fabricate material to their individual specifications, while making customer service and fast turnaround times a high priority.

The company has survived economic depressions, world wars, labor disputes and market fluctuations, and continues to cut, drill and blast on Rattlesnake Hill.

When John Swenson died, the vision that he started did not, and is carried on by his descendants.

“His loss would be felt even more keenly had he not left behind sons who will continue and increase the industry which he created,” The Concord Monitor wrote upon his death.

But to the Swensons who remain, what’s even more enduring than the family is the granite itself. Geologists estimate, Concord workers have dug 200 feet down into Rattlesnake Hill. They figure they have at least 1,200 feet to go.

“Some days it seems we have an endless supply of granite,” Kevin Swenson said. “It will outlive all of us.”